Table of Contents

- Unpacking James Lovelocks Vision: Democratic Ideals and Environmental Challenges

- The Intersection of Gaia Theory and Governance: Insights from Lovelock

- Evaluating Lovelocks Critique of Modern Democracy: Lessons for Policymakers

- Navigating Complexity: How James Lovelocks Ideas Can Inform Future Democratic Practices

- Practical Recommendations: Implementing Lovelocks Concepts in Contemporary Democracies

- Q&A

- Final Thoughts

Unpacking James Lovelocks Vision: Democratic Ideals and Environmental Challenges

James Lovelock, renowned for his Gaia hypothesis, often delved into how democratic ideals intersect with environmental imperatives. He posited that traditional democratic processes might struggle with the urgency required to address ecological crises. Lovelock suggested that the extended timelines and compromises inherent in democracies can be at odds with the swift action needed to combat climate change. This perspective invites a fresh discussion on balancing individual freedoms with collective ecological responsibilities.

Lovelock’s reservations about democracy, however, shouldn’t be mistaken for a wholesale rejection. Instead, he called for an evolution of democratic processes to better meet ecological needs. To accomplish this, a few key changes could be implemented:

- Policy Innovation: Encouraging innovative policy solutions that are ecologically sound and practically feasible.

- Integrated Technology: Leveraging technology for transparent decision-making processes that engage citizens while accelerating policy implementation.

- Inclusive Dialogue: Facilitating more inclusive public dialogues that prioritize environmental issues alongside economic and social concerns.

His vision also implied the need for a global approach to environmental challenges, perhaps requiring democracies to cooperate beyond conventional boundaries. To illustrate how different democratic models can address environmental issues, we can explore various governance structures:

| Model | Focus | Potential in Environmental Policy |

|---|---|---|

| Participatory Democracy | Citizen Engagement | Empowers local communities, encouraging grassroots movements for sustainability. |

| Representative Democracy | Delegated Decision-Making | Allows balanced policies through elected officials, but needs quicker response mechanisms. |

| Ecological Democracy | Environmental Prioritization | Places ecological concerns at the forefront, but requires broader acceptance and understanding. |

This nuanced examination of James Lovelock’s theories encourages us to think critically about how our political systems can adapt and thrive given the mounting environmental pressures we face globally.

The Intersection of Gaia Theory and Governance: Insights from Lovelock

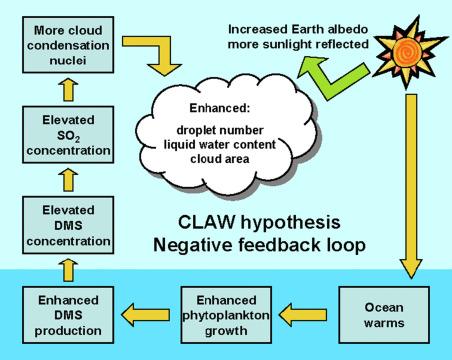

In the tapestry of environmental and political discourse, James Lovelock’s Gaia Theory has woven a profound narrative that intersects with governance. Gaia Theory, positing the Earth as a self-regulating complex system, isn’t merely about ecological balance. It offers a framework that underlines the interconnectedness of systems—a concept that can seamlessly translate into governance. Just as Gaia maintains stability through a network of interactions, governance structures benefit from recognizing interdependencies among social, economic, and environmental policies. Gaian principles can enhance policymaking by fostering a holistic approach, emphasizing sustainability, and acknowledging the limits of growth.

Lovelock’s insights could inform governance paradigms in several ways:

- Adaptive Policies: Similar to Gaia’s adaptability to changes, governance should emphasize flexible policies that can evolve with new scientific data.

- Systems Thinking: This approach encourages viewing society through an ecological lens, focusing on feedback loops and the impacts of decisions across various sectors.

- Collaborative Governance: Advocates for inclusive decision-making that mirrors the diverse interactions found within the Gaia system.

Embracing these concepts can lead not just to resilient environmental strategies, but also to robust democratic frameworks. A government informed by Gaia Theory might prioritize long-term well-being, balance stewardship with innovation, and cultivate a political ecology that is both dynamic and inclusive. Here’s a simplified illustration of the core principles:

| Core Principle | Application in Governance |

|---|---|

| Self-Regulation | Decentralized decision-making processes |

| Interconnectedness | Integrated policy frameworks |

| Adaptability | Dynamic legislative processes |

Evaluating Lovelocks Critique of Modern Democracy: Lessons for Policymakers

Lovelock’s insightful critique provides policymakers a lens through which we can examine the fundamental structures of our political systems. He raises concerns about the current democratic frameworks being too sluggish to effectively tackle urgent and complex issues, such as climate change. This critique challenges policymakers to think beyond the traditional binaries of decision-making and consider more adaptive models that reflect the rapid pace of modern challenges. By doing so, we ensure that democratic processes are not only representative but also resilient.

To address the core issues identified by Lovelock, policymakers might consider implementing strategies that include:

- Enhancing Public Engagement: Encouraging diverse voices in decision-making to ensure more holistic outcomes.

- Flexible Governance Structures: Evolving policies that allow governments to quickly adapt to new information and challenges.

- Sustainability Focus: Integrating environmental considerations into all policy discussions.

Another key aspect is fostering a culture of collaboration over competition within political entities. A comparative look at decision-making models might reveal:

| Model | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Consensus-Based | Inclusive, Encourages Dialogue | Time-Consuming |

| Majority Rule | Efficient | May Marginalize Minority Voices |

This comparison highlights the delicate balance policymakers must maintain to ensure democratic systems are both effective and equitable in addressing contemporary global issues.

Navigating Complexity: How James Lovelocks Ideas Can Inform Future Democratic Practices

James Lovelock, known for his groundbreaking Gaia hypothesis, offers intriguing insights that could potentially revolutionize democratic practices. His ideas, which emphasize the interconnectivity and self-regulation of systems, can be applied to political structures to enhance their resilience and adaptability. Just as ecosystems maintain their balance through diverse elements working together, democratic systems might benefit from more integrated and holistic approaches to governance.

Incorporating Lovelock’s concepts into democracy might involve adopting a more systemic viewpoint, where solutions are informed by the complexity and interconnectedness of societal issues. This approach encourages the inclusion of varied perspectives and expertise, fostering environments where diverse voices contribute to decision-making processes. Some key practices influenced by his thinking could include:

- Adaptive Governance: Encouraging flexible decision-making that responds swiftly to changing conditions.

- Participatory Models: Enhancing civic engagement through diverse pathways, ensuring a more representative governance.

- Systems Thinking: Applying holistic strategies that consider the interconnected nature of modern challenges.

Future democratic practices might also benefit from examining the balance between technological advancements and ecological considerations. Lovelock warns against technology’s unchecked intervention, suggesting that democratic frameworks need to evolve in ways that respect the planet’s natural systems. By integrating ecological consciousness into democratic practices, societies can work towards solutions that are sustainable both for humanity and the environment. In this context, a framework of hybrid governance may emerge, where technology and human adaptability work harmoniously within the confines of Earth’s ecological laws.

Practical Recommendations: Implementing Lovelocks Concepts in Contemporary Democracies

Integrating James Lovelock’s visionary ideas into the framework of modern democracies requires a blend of innovation and practical application. Lovelock’s Gaia theory, which emphasizes the interconnectedness of Earth systems, can inspire governments to adopt more holistic policy-making approaches. One way to infuse these ideas into democratic practices is by expanding environmental legislation that recognizes the symbiotic relationship between humans and the planet. This could involve establishing multidisciplinary advisory panels to guide policy, ensuring decisions take ecological sustainability into account while balancing economic and social factors.

Democracies must also prioritize the engagement and education of citizens to foster a collective consciousness aligned with Gaia principles. Educational curricula should integrate lessons on planetary stewardship across various subjects, encouraging a new generation of environmentally conscious citizens. Moreover, creating platforms for public engagement—such as interactive town halls or online forums—enables individuals to voice their opinions and participate actively in environmental management. Technology-driven initiatives, like mobile apps, can disseminate actionable information, empowering communities to implement sustainable practices at a local level.

On a structural level, adopting Lovelock’s concepts can lead to innovative governance models. For example, introducing policy instruments that incentivize reduced carbon footprints can drive systemic change. In truth, understanding and acting on the urgency of environmental challenges require governments to operationalize a blend of strategic incentives and regulations. Implementations like carbon credits or community renewable energy projects could raise environmental awareness and initiate collaborative climate solutions. Furthermore, leveraging public-private partnerships can spark pioneering developments in sustainability practices, diminishing the traditional barriers between governmental frameworks and ecological paradigms.

0 Comments